Houseless in KC

Season 1 Episode 102 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Explore community efforts to end homelessness in Kansas City.

Over the last year and a half, efforts to end homelessness have accelerated in Kansas City. The team at Flatland takes a look at how service providers, city officials and those experiencing homelessness are coming together to form both short and long-term solutions as winter approaches.

Flatland in Focus is a local public television program presented by Kansas City PBS

Local Support Provided by AARP Kansas City and the Health Forward Foundation

Houseless in KC

Season 1 Episode 102 | 26m 46sVideo has Closed Captions

Over the last year and a half, efforts to end homelessness have accelerated in Kansas City. The team at Flatland takes a look at how service providers, city officials and those experiencing homelessness are coming together to form both short and long-term solutions as winter approaches.

How to Watch Flatland in Focus

Flatland in Focus is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

More to Explore

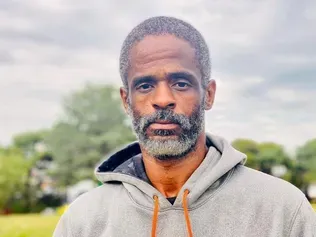

Meet host D. Rashaan Gilmore and read stories related to the topics featured each month on Flatland in Focus.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for civic affairs programing on Kansas City PBS is made possible in part by AARP Kansas City.

Hi, I'm Dee Rashawn Gilmore, welcome to Flatland.

Every month we dig into one issue raising questions, causing tensions or, quite frankly, has gone curiously unexplored in our area for this episode.

We'll be talking about houseless -ess in Kansas City Over the last year, homelessness has never been far from the headlines in Kansas City, after Scott Eiki froze to death in his tent last winter and advocates for the first homeless union of Kansas City.

City officials mounted an unprecedented response.

Bartle Hall was opened as a warming center for hundreds of unsheltered people.

Up to 500 hotel rooms were available for 90 days.

Meanwhile, the City Council grappled with longer term solutions, such as creating a tiny home village.

But as emergency programs come to an end, many found themselves back out on the streets and encampments where they face the near-constant threat of sweeps.

With winter approaching again, let's take a look at how servic providers, city officials and those experiencing homelessness are coming togethe to form both short term and long term solutions.

Bartle Hall was a great idea in theory, and we met our goals and objectives of the winter of having nobody die on the streets of our city because they didn't have a place to stay.

Bartle Hall at some point ended in the hotel program we did this spring.

At some point ended through those two things.

We provided a lot of services and support to people who did not have it.

Where are they after that?

There are still people that we weren't able to serve.

I grew up in foster care, right?

You know, I move constantly.

I have emotional and psychological issues where I can't maintain a place to stay very well because I'm always terrified that someone is going to come and tell me it's not for me.

I lived in my vehicle for a long time.

I drove around the country, so we saw that.

So if you see my van out there, it's a white 93.

Ford Econoline 150.

Yeah, I'd like back.

Without a home, your brain shuts down and goes into just survival mode.

You can only think of the very next thing that you absolutely need.

You got a piece as you just think of until you get don if you're hungry.

That's what you think of until you can only go from from point great point planning ahead, falls out the window you know, and you start making poor decisions.

Not because you're less smart because your brain functions on this level that says, Look, I've only got this little bit of whatever.

I'm going to enjoy it as much as I can.

And you end up, it turns into an instant gratification thing.

So I recognize the difference in stability.

I feel it when I have stable housing.

I see the change in the way my brain operates when I have stable housing.

I was part of the hotel initiative, so those three months were nice and stable at the end of the hotel initiative.

Less than a third were house.

Instead of creating some sort of situation that provided housing for these people and prevented homelessness.

They put them right back out on the street.

We still wanted to be visible.

We still wanted to make a point, so we moved to Eloise Davis Park.

They swept us three times there.

There's no dustpan for us.

Do you know what I'm saying?

You're just pushing dust around the house.

Until we have homes, we have nowhere to go.

The park shelter order is actually completed.

It's been completed for a couple of months.

It's sitting in Washington.

When Verge first started being in planning, we met with different ways for months and just said, Hey, we're in the area.

We're talking about building this project somewhere around North East, or it could be in the east bottoms, west bottoms.

We're not sure we just want to keep it somewhat centrally located.

And everybody was super supportive right out the gate.

They had a special committee that was created.

And then when I went to City Council Hall, that's when kind of the naysayers were kind of twist in their own council members arm saying, No, we don't want this because we're too close to our neighborhood.

That wasn't ever the plan.

We were actually been looking at commercial zone properties since the start.

And then it was like more pushback, like, well, this is going to cause too much crime, any of the neighborhoods when in reality, police departments and cities that have done this are showing a huge drop in calls, just like KCPD really has thousands of suspicious party calls one of those are start going away.

If there's nobody suspicious.

Hanging around downtown is really just a houseless guy trying to be warm.

see tents and they see homeless people living in certain places out on the street and they ask cities to remove them.

But they also don't want to build facilities and structures and resources locally in those neighborhoods.

They're everywhere and they're in all neighborhoods, and we need to provide those types of services and housing and support in all neighborhoods.

We are here because we want to utilize our knowledg and our experience to change the way they do thing at the top of the hill.

You know what I'm saying?

A housing first approach.

Get them off the street.

Creating a stability is the first step in being able to find out what's really wrong.

The system is set up for you to go from street to shelter, from shelter to transitional living and from transitional living to permanent housing .

But there are massive barriers between each one that prevents success from happening that prevents street from becoming permanently house.

Let's just start with shelter shelters fill up really, really quickly.

And if the doors open around five, you need to be in line around 3:00.

If you're not in line at three, you will not get a bed.

So what does that do for your job prospects?

Do I quit my job so I can have somewhere to sleep tonight?

Or do I keep my job and I sleep on the streets?

And it's a barrier that's in conflict with what the general public believes that homeless people should do.

They should work.

Now let's go from shelter to transitional living, so think about all the things that you need to get into an apartment.

You need an ID.

You need credit history.

You need references.

I have never met a homeless individual that hasn't had every one of their identifying documents stolen while at a shelter.

Do you have to attend classes?

There's often a religious component, and you have to do us frequently.

They're going to look and see if you've done drugs or alcohol and if you fail that way, you don't go back to the shelter.

You go back to the street and you have to start that entire process over again.

Now, let's say you manage to get all the way through to help and you have enough money saved and you're able to go into permanent housing.

Let's describe the type of person that is effective through this system.

It's someone who has gainful employment from the hours of seven to thre and someone who has all their identifying documents .

It's someone who doesn't drink or smoke.

It's someone that has good references, has good credit and is able to routinely keep a schedule because it doesn't sound like we're describing people who need help.

It sounds like we're helping people who have it pretty good, and they send you back to the streets with this thought.

That'll show them, that'll show them next time.

They won't do that.

But on the streets, what are they getting?

You sleep about three hours a night.

It's unsafe.

You're not eating, you're probably self-medicating You're probably going to lose your job.

How are you going to pay for that phone you got?

You need to stay in communication with the network that you're building.

It's a failed system.

It's completely failed and it's backwards.

And that's why I'm moving permanent housing closer to st. Is the right move My name's Jamal Collier.

I'm from Kansas City, Missouri.

Been homeless three years and now I'm with the Lotus team Lotus Team Care House, There go the little Lotus cat.

She pregnant.

It makes me feel it makes me feel like it's the reason why I'm working three jobs.

It's the reason I want to keep going because it gives me an opportunity to be outside of myself, but then also to be able to have someone safe to come back and be myself.

And that's everything, man.

And I was away there for five years.

I got laid off because of Covid, when you want to go, look for work, it doesn't come easy.

Yes, I have felonies.

Yes, I'm big black and got tattoos.

I had to.

So all of these, a lot of those bad marks for me And even though I paid my dues to society, some people are intimidated, bu I can't really see a way out of this other than to really build a community.

This right here is the compensation.

And that's a first for me.

You know, so what we're trying to do is really define kind of what the values we hold here.

Lotus Care House, what do you think are the six most kind of values that resonate with you?

The melody, community, creativity, balance, stewardship, compassion growth and resilience.

I think there has been a lot of lessons learned this past year.

The Navigation Center is just one part of a housing employment ecosystem that we're trying to build.

Figuring out how do we all work together because we all come from very different points of experiences, different points of expertize.

But how do we really work through those challenges so that, more importantly, no one dies this winter and that we can keep people safe?

The gears of government turn slowly, to be honest, but they do turn and we are making some progress and we're really excited about over even the next few weeks.

Some initiatives that we're going to announce here to build more permanent housing, things that we've never had before, and to incorporate it into our standard practices of finding homes for people.

You know, we're still in the final stages of doing the RFP evaluation process on it related to building permanent, supportive housing at a large scale in several parts of the city.

We're hopefully soon going to be hiring for the first time, first ever tenant advocates, first ever people dedicated to homelessness support and reducing homelessness, creating and preserving affordable housing staff that we've never had dedicated to this stuff.

We're collaborating with Casey tenants to make sure that we get the right structure in place, to make sure that those new residents have the rights and responsibilities and and and authority that they need to live self-sustaining sufficient lives in their homes to make sure that we're doing it right.

City is eager to do something about it.

You know, however, you know, time is sensitive right now and we have to act accordingly.

We are not out here trying to die.

The cavalry ain't coming.

We all we got winners come every day is getting a step closer and we don't know where the city stand and we are in a race for our lives.

Welcome back for the discussion portion of our program.

With us in studio today is Brian Platt's, city manager of Kansas City.

Marqueia Watson, director of the Greater Kansas City Coalition to End Homelessness.

Jamal Collier, program advisor at Lotus Care House, who has experienced homelessness himself.

And Myranda Agnew, director of the Leavenworth Interfaith Community of Hope.

What do you wish city leaders in particular understoo about what it's like to experience homelessness?

What it feels like to have hopelessness, because, man, at the end of the day, you feel like you have no options.

You can't even so much as lay down at a bus stop just to get some rest if you have nowhere to go.

So it becomes like restlessness, which can turn into you getting delusional exhaustion.

It makes a lot of people wanted to commit suicide It makes a lot of people want to give up completely and just stop the game at all.

I think if we had a way of giving somebody hope and as well as shelter and is not being forced by religion or all, you have to meet these requirements.

You can't because some people can.

Some people mentally can't Some people emotionally can't, physically can't, you know, and some people just need help.

What are the issues and challenges that service providers are facing and trying to address the issues that Jamal just spoke of?

This might sound kind of silly and basic, but I think that the biggest challenge is that we don't have enough adequate, affordable and decent housing for people and in particular for people who are single without children and within the constraints of the fair market rents in particular, you know, that's around seven or $800 a month, depending on the funding source And so finding decent housing for folks in that price range is becoming increasingly challenging.

Housing folks without the ability to get them connected immediately to behavioral health Is this really problematic for And can you help our viewers to understand what it is exactl that the Greater Kansas City Coalition to End Homelessness does and the role that you play in the work that you just described.

We are the lead agency for the local HUD continuum of care And so we're charged with organizing and convening the homeless work in Jackson County, Missouri, and Wyandotte County, Kansas.

So that has a lot to do with the federal grant making process for continuum of care funding, but then also conducting our annual census of homelessness, working on a regional strategy around ending homelessness, working with our service provider community, our medical community, faith leaders, city officials, all of those types of folks.

And increasingly we're emphasizing also collaborating, meaningfully collaborating with people with lived experience such as Jamal, who obviously are the experts in what it is that we should be doing.

Brian Plante, Mr. City Manager You have a very unique role in all of this.

And on the one hand, you're dealing with a community and not just those who are homeless or unhoused, but also the broader Kansas City community that has questions and concerns about this issue.

And then you also have the very intricate dance that you have to do with the 13 members of the City Council, including the mayor that are effectively your bosses.

How are you navigating those waters to bring about the kind of changes that both Jamaal and Marqueia spoke of?

I'll say that I think that everyone who that I've interacted with here does want to make some sort of positive change and improvement in the way we're providing services to this community.

I think that sometimes we disagree on what that change is and should be and how we go about doing that.

We set a goal of 10,000 new affordable housing units in the next five years.

This is an ambitious and aggressive goal, but we have to be we have to be bold and innovative and aggressive in our actions here and our steps here, because this is an issue that has not started this year, but it seems to only be getting worse at this point.

The pandemic has certainly exacerbated it.

Well, let's drill down on that a little bit.

You mentioned the goal of 10,000 housing units, which would be amazing.

I think we'd all like to see that.

But how do we pay for it?

I mean, the city took a big hit to its budget last year, dealing with a lot of COVID related issues and thinks How do we get to those 10,000 housing units?

For example, we've got 2000 city owned vacant lots across the city.

How do we turn that into housing?

How do we get someone to build affordable housing on those blocks?

We've got hundred vacant homes, abandoned homes in the city owns.

We've already issued an RFP where the city selling those for $1 provided that the new owners turn those into affordable housing.

We're looking at city owned property that other projects that we've got, for example, we've got a parking deck at Barney Alex Plaza next to the convention center.

It's going to cost us $80 million already to renovate and rehabilitate that structure Why not add additional community benefit by way of affordable housing on a site like that that we've got, of course, an inclusionary zoning ordinanc at an affordable housing trust fund that we set aside to help incentivize and push for more affordable housing units in regular market rate multifamily developments.

And we've got to think ab out more ideas like this.

We're thinking about also tiny homes.

And also we.

Just issued an RFP a few months ago that will hopefully create additional low ultra low income housing for the homeless and those who are at the lowest income levels.

one of the options there that we're thinking about, for example, is taking a hotel and turning it into permanent, supportive housing.

You know, the units are a little smaller, but at least you're getting a roof over someone's head and at a fraction of the cost of building new housing.

But Jamal, I'm wondering, you have experienced houselessness before you are working with others who who do as well?

Does this sound like some new, ambitious, aggressive, innovative goal or does it sound like more of the same to you?

Be honest, it does sound like they're trying, but it is more of the same because none of the things that I've heard have worked because, yes, the lady was saying earlier, there is a lot of mental issues that people are dealing with this drug issue.

There's people deal with neglect better, you know, things that you know to where they feel like there's no hope in the whole thing is giving a person hope.

I had hope.

I've been chasing my music career before I was homeless while I was homeless.

And after, you know, it's a little bit more aggressive now because I have a little bit more force.

I'm working three jobs.

But without that hope, a per- -son would be like whats the point in even trying?

If the program came with something to incentivize or something that would touch on passion or touch on creativity, or touch on things that people really live for, like you give a person that option in the midst of where they're at It's something that they could smile or look forward to, or see a better version of themself that is going to create momentum within their spirit is to push them and make them be more.

You know, I think there's something very something very, very important here.

I want to bring Miranda Agnew into the conversation here.

The interfaith community of hope, I mean, hope is at the core of what Jamal just described, because if you have hope, you have options.

What is the role of the faith community in all of this?

And do those things?

I know there are a lot of places that have this sort of litmus test.

I mean, you've got to be these five things before you can even walk in the door and get a roof over your head.

How are you approaching that work in Leavenworth and what lessons from your work might we be able to learn from or apply here in Kansas City?

Ultimately, if I could sum it up, it's relationships because I think when we talk about housing one here in a smaller community, housing is tough because like everybody's mentioned, you know when rent is seven or $800 and you're somebody that has gotten disability and your disability check is $700, you're never going like, we're crazy to think that you're ever going to keep succeeding when you're your income matches, just paying the bills for your house.

So we really here are focused on attainable even in affordable housing.

But even more than that, it's listening to our individuals because we've got plenty of individuals that could move out tomorrow.

And if they, you know, we can help them with the funding, they would be fine We've got other individuals who we have moved out.

They lost their community.

They were completely alienated.

We don't have where are the only public transportation in Leavenworth?

So when we put them in a in a home, in an apartment, they almost lose every service that's available to them because to get back to us, they have to have housing.

And the free food pantries are all downtown Leavenworth.

And maybe that's not in walking distance, especially for individuals who are in wheelchairs.

Maybe housing is the option, but in plenty of spaces, it's not a first for Jamal.

You're absolutely right that sometimes we have to have hope for people until they have an opportunity to have it for themselves.

You know, and I think thinking more aspirationally about people's potential and their possibilities rather than what's wrong with them is a big part of, I think, what's broken about the system that's designed to help people and in fact, that we often harm people by not seeing them in their fullest potential or limiting them in such ways that getting SSDI or SSI and getting a Section eight voucher is the end goal for people.

And we all have so much more human potential than that.

So I'm curious, though, when we talk about issues around the local ordinances and things, what can be changed to minimize the harm that comes to people who experience homelessness so they're not criminalized for simply not having a roof over their head?

Yeah, this this is an issue that really harasses my thoughts quite a bit because, you know, most systems are most legal systems are punitive towards people who don't have housing when really, it's not the fault of the person that we've created these structural barriers that that harm people and keep them isolated and alienated from the rest of us.

And so I I'm on the actually on that Kansas City Health Commission and on the Ad Hoc Committee on Housing.

That's an offshoot of that commission, as well as the mayors appointed task force.

And so we're all talking about these issues and in particular around House Bill of Rights, which is right now it's at the at the city's legal department being scrutinized.

And I think that at some point in the very near future, it will go in front of council for consideration.

But essentially, it's predicated on the UN's charter on human rights and the idea that housing is a human right and that people.

Have the right to dignity and safety and all those things but then also we've identified through the pandemic that we have a significant issue around race that's driving our homelessness and that we have to be mindful of those isms that are keeping people out of housing so homophobic.

Some cisgender ism, all of that type of stuff, in addition to racism, is also embedded in the charter And I'm really excited to see that we've been working also with our houses community on bedding the language and ensuring that it really speaks to their needs But at the end of the day, really, we just don't want to be a society that punishes people for not having enough and that people need to, like Brian said, have a place to live and to sleep and before they can start working on those other challenges.

I'm wondering if you would be willing to just speak to the audience just sort of broadly, not just the panel assembled here.

What do you most wish that people understood about homelessness and what it is like to experience it?

Wish people understood, just like they enjoy getting off of work, coming home, relaxing in their comfort, in their bed, in their own living space.

Another human person would like to share those same things, whether they have mental issues, whether they've been raped, abused, cast out or judge.

I think if we had a lot more compassion in our community, it would help a lot of things showing compassion and literally becoming a fan of every homeless person b So they have at least one fan who knows it could start a wildfire.

And everybody feels that way about this person because one person saw potential in every month on our website, we answer your questions about life in Kansas City and issues you care about through our CuriousKC initiative Let's hear from our community reporter Vicki Diaz Camacho about our question of the month This month's CuriousKC question question was submitted by John M. He asked, Isn't it cheaper to provide free housing for Kansas City's unhoused population rather than spending money on 911 calls an emergency medical services?

It's less expensive in all the ways, not just about this fiscal perspective, but also the human cost of having people living on our streets , I think is is incalculable.

And it's an issue that impacts everybody.

It's really a reflection on our value system as a community that we have this pervasive issue and an issue that's growing and we know that it's cheaper to house people, but we also have a moral obligation to do so.

And that's where we wrap up today's conversation and this episode of Flatland.

You've been listening to a city manager, Brian Platt, Marqueia Watson from the Greater Kansas City Coalition to End Homelessness.

Jamal Collier of Lotus Care House and Miranda Agnew from Leavenworth Interfaith Community of Hope.

Thank you for joining us.

Please stay up to date on our series and submit your curious case the question for our next episode's topic on Flatland Show dot org.

We're also excited to announce our participation in the KC Media Collective, a nonprofit media collaboration with Casey.

You are the Beacon, Star News Missouri Business Alert and American Public Square.

Visit Flatlandkc.org/kcmc for more information about this exciting new initiative and to learn more about our partners.

This has been Flatland.

I'm D. Rashaan Gilmore.

Thank you for the pleasure of your time.

Bye bye!

Support for civic affairs programing on Kansas City PBS is made possible in part by AARP Kansas City.

Flatland in Focus is a local public television program presented by Kansas City PBS

Local Support Provided by AARP Kansas City and the Health Forward Foundation