Finding Your Roots

The Road We Took

Season 12 Episode 4 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

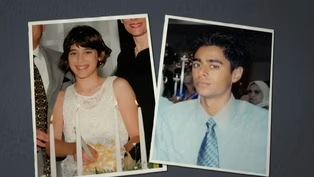

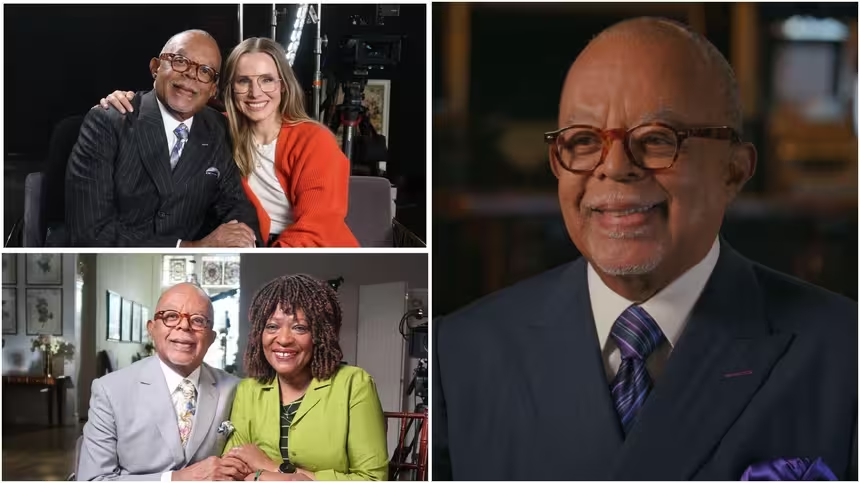

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the roots of actor Lizzy Caplan and comedian Hasan Minhaj.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the roots of actor Lizzy Caplan and comedian Hasan Minhaj, uncovering ancestors who made brave decisions that forever reshaped their family trees. Moving from shtetls in Eastern Europe to farmlands in northern India to the shores of the United States, Gates introduces his guests to the women and men who overcame enormous hardships to find a better future.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

The Road We Took

Season 12 Episode 4 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the roots of actor Lizzy Caplan and comedian Hasan Minhaj, uncovering ancestors who made brave decisions that forever reshaped their family trees. Moving from shtetls in Eastern Europe to farmlands in northern India to the shores of the United States, Gates introduces his guests to the women and men who overcame enormous hardships to find a better future.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to “Finding Your Roots.” In this episode, we'll meet actor Lizzy Caplan and comedian Hasan Minhaj, two people whose families have been shaped by immigration.

MINHAJ: I grew up seeing the sacrifice it takes to make the American dream possible.

CAPLAN: I have thought about, you know, what it would be like to be on a boat coming to a place where you knew nobody.

GATES: Yeah.

CAPLAN: It's totally unimaginable.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

MINHAJ: No, this is incredible... I don't, how did you guys find this?

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

CAPLAN: No way.

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a “Book of Life,” a record of all of our discoveries, and a window into the hidden past.

So, you thought of yourself as Russian?

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: Did you ever think of yourself as Polish?

CAPLAN: No.

GATES: You're Polish.

CAPLAN: Yeah!

MINHAJ: It's making me think about a lot of the decisions that I made in my life, and maybe that courage and conviction came from my ancestors.

GATES: My two guests both descend from people who had to grow up fast, find their way across the globe, and build a new life in a new country.

In this episode, we're going to retrace those journeys and recover what was lost along the way.

(theme music playing).

♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ GATES: Hasan Minhaj is on a roll.

The mercurial comedian has won two Peabody Awards and garnered a legion of fans by blending stories about himself and his family with keen observations about Muslim life in America.

MINHAJ: My dad sits everybody down at the dinner table, and he's like, “All right, Hasan, whatever you do, do not tell people you're Muslim.

Do not talk about politics.” I was like, “All right, dad, I'll, I'll just hide it.

Cool.” GATES: It's a brilliant act, and he's been refining it since he was a child.

Growing up in Sacramento, California, Hasan was a class clown, often in trouble with his teachers, perhaps because his home life was quite restrictive.

Hasan's mother had returned to India soon after his birth to finish her studies.

So, he spent his first eight years in the care of his father, a man who had a lot of rules.

So how do you think that affected you?

MINHAJ: Um... GATES: To me, that would be a nightmare, I mean, my parents are dead, I love you, Daddy... MINHAJ: Yeah.

GATES: ...But I wanted my mama love.

MINHAJ: Yeah, so, you know, with, with me, with me and dad, you know, look, Doctor, we can get into this, and I don't know if you're a, if you do psychology, but the, the level of draconian law is pretty crazy.

GATES: That's 'cause he had a crazy kid.

MINHAJ: Yeah.

GATES: You know, you're outta control.

MINHAJ: Yeah, but no touching the thermostat.

No video game consoles?

No cable television.

GATES: Oh.

MINHAJ: Um, oh, yeah, yeah.

GATES: Now we we're getting closer to, uh... MINHAJ: Oh, yeah, Sacramento, you, you know how hot Sacramento is, Doctor?

It's incredibly hot.

We can't touch the AC; there's oscillating fans in the house.

Four oscillating fans don't touch the, the thermostat.

So, I, I, even though I lived in the suburbs, our house was like a trap house without all the fun of cooking cracker meth.

(laughter).

You know, this is the type of man this was, this guy was.

GATES: Though Hasan didn't know it yet, his father would actually help launch his career.

He started doing standup in college with material drawn from his family, but fearing that his parents wouldn't approve, he tried to conceal it.

MINHAJ: My mother and father did not know I was doing this at the time.

GATES: Uh-huh, so if they didn't know, when did they know?

MINHAJ: They found out when I took my dad's car, and I totaled it on the way to a comedy gig.

Then, unfortunately, they found out, I said I was at the library, um, but I was on the way to Tommy T's Comedy Club in Pleasanton.

GATES: Now, how old, when was this?

MINHAJ: Um, I'm like maybe a junior in college, yeah, yeah.

And my dad, I had to call my dad to come get me, and he goes, “Wow, we're about 40 miles from the library?

You sure you're going to the library?” (laughter).

GATES: With his secret out in the open, Hasan was able to devote himself fully to his craft.

After college, he began releasing videos on YouTube, which led to a spot on the “Daily Show” and a breakout special on Netflix featuring a routine that was largely focused on his childhood.

The only problem, his parents still didn't know exactly what he was doing.

Did you tell your parents about it before you let them see it?

MINHAJ: They came to the off-Broadway show in New York, so by the time it was up and running, they finally... GATES: So, what was their reaction?

Because it's about them.

MINHAJ: Yeah, um... GATES: Were they hurt?

MINHAJ: I would say, it's very complicated, 'cause it's a lot... GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: On one-on-one hand, they're proud.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Like, I remember seeing my parents at the show, they're looking at other people to be like, “Wait, they're all here to see him?” GATES: Right.

MINHAJ: So, they're acknowledging that.

GATES: Right, right.

MINHAJ: Right?

And then at the same time, there's a level of like, “Hey, why are you, why are you talking about this stuff?” GATES: Yeah, right.

MINHAJ: “And why are you making it more dramatic?” GATES: Right.

MINHAJ: You know, like "You're really, you're really hamming it up here..." GATES: Right.

MINHAJ: "...for them, and why are you doing that?"

So, there's all these layers to it, which is, there is, there is this simultaneous like wonder... GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Curiosity, awe, pride, and “Why do you have to do this?” GATES: Yeah.

MINHAJ: It's like five different emotions going on.

GATES: Do you and you sensor yourself... MINHAJ: Sure.

GATES: ...because of that?

MINHAJ: A little bit.

GATES: Little bit.

MINHAJ: There's, there's a, there's, there's some things that I will change or modify or cut or truncate.

GATES: It'd be too, too painful.

MINHAJ: It'd be too painful, and also, you just want, like, these are people that I love.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: You know, they're ultimately, they're people that I really love, and I want them to be happy.

And we have, we have so much else to fight about.

We, it doesn't have to be about the act, yeah.

GATES: My second guest is actor Lizzy Caplan, who came to fame in the cult classic “Mean Girls.” (vocalizing).

(crowd cheering).

GATES: And has built a remarkable career by crafting a series of unforgettable offbeat characters.

CAPLAN: Oh, I'm sorry.

Did you think that I was like those other girls?

GATES: Lizzy is blessed with impeccable comic timing, but her own story begins in tragedy.

As a child, Lizzy's world was turned upside down when she lost her mother to cancer.

CAPLAN: She was sick for a year.

Uh, it still was a great shock to everybody.

She was young.

She was 50.

GATES: Can I ask you how you coped?

I can't imagine that losing my mother at that, at that age.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

Not well, I mean, it's, it's funny when, when people lose a parent, funny, obviously not funny ha-ha, but when people lose a parent and, you know, everybody says, “Oh, that's such a horrible age.” I don't know when a good age would be.

Uh, if you're very small and you never really have any lasting memories of that person, that's its own tragedy.

And then for me, I was 13, you know, right on the cusp of womanhood like an adolescent, and that was pretty bad.

That was a pretty bad time for it to happen; I was very close with my mother.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: All of my siblings were; she definitely was the center of the family that kept everybody together, and when she passed away, we kind of all lost our way as a family for quite a while.

GATES: Lizzy would ultimately find her way, but it took more than a little luck.

Soon after her mother's death, she was accepted into an arts high school in Los Angeles.

She was supposed to study piano, but lost interest, so she switched to acting and discovered her calling.

CAPLAN: I just liked it.

Certain things came sort of easily to me, learning lines and diving into a character, um, and I also think, you know, in retrospect, I've, I've thought about this, that in my sort of angst-ridden teenage brain, I was actively trying to make sense of my mother's death.

Why did this terrible thing happen to me?

And in my mind, I mean, I wanted nothing to do with doing comedy, I was gonna be a serious actress and Shakespearean actress, and I needed to have this like, trauma and darkness and depth in order to access these parts of myself.

And I think, honestly, it probably got me through a lot of, a lot of that time.

Um, because it was me just trying to like attach meaning to this horrible thing that happened.

And the way that I attached meaning to it was, “Oh, I need this darkness to pursue this acting thing.” GATES: Lizzy may have been wrong about her future with Shakespeare, but she quickly found another outlet for her talents.

Although her father had no connections to the entertainment industry, she had an uncle who was a publicist.

So, she turned to him for help, and that would change her life forever.

CAPLAN: He introduced me to this manager he knew, but it was like the, the lowest assistant on the totem pole of this tiny management company.

And this guy agreed to sort of represent me, probably as a favor to my uncle.

GATES: Right.

CAPLAN: And I started going out for auditions, and I just, I started getting jobs, but not anything like, in my mind, I was gonna be the lead of the show, and it was gonna be like, shot out of a cannon.

And it was not that.

It was, you know, my first job was one line, “girl number one” in a pilot.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: And it just gave me enough, like, not enough to be fulfilling, but enough to like, "Just keep going, just keep going a little, just a little, see what happens, see what happens."

And for whatever reason, I never like doubted that that was gonna be my thing.

GATES: Huh.

CAPLAN: And I, I don't know, I think probably only in recent years do I think, oh, okay, maybe I, maybe I, I feel good about the work that I'm doing, and maybe this was what I was supposed to do, as opposed to like, well, I can't do anything else.

GATES: Right.

CAPLAN: I got no college education, I have no plan B. Like, what am I gonna do?

GATES: Right, yeah.

CAPLAN: Um, but I, I also just genuinely love doing it, I love it as much as I'd probably, I mean, more so, than when I was a kid.

It just was an instant fit.

GATES: My two guests have been fortunate.

Both have thrived in the public eye, finding fame and fulfillment in the limelight, but their family trees are filled with people whose stories have long lingered in obscurity.

It was time for that to change.

I started with Hasan and with his father, Najme Minhaj.

Najme immigrated to the United States when he was 31 years old, seeking work as a chemist.

But Hasan believes that his father's job was never the most important thing in his life.

MINHAJ: I went to his retirement party, and his coworkers gave speeches, and we cut Costco sheet cake.

(laughter).

And then they were like, thank you for the 35 years.

GATES: Did he cry?

MINHAJ: No, he didn't cry.

But I was really moved.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Because I, I kind of looked at his office and his floor and I was like, man, like, you know, it's just a sea of cubicles.

It looks like the TV show “Severance.” GATES: Hmm.

MINHAJ: You know?

GATES: Oh, wow.

MINHAJ: It's just a sea of cubes.

And I was like, "Man, my dad came here every day, he took the light rail or the bus, and he had this job that I'm sure he, I know he did not like, but he did that all for me."

GATES: Wow.

MINHAJ: And my sister.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: And I see my dad still to this day as someone who is obviously extremely intelligent, but has so much potential.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: And, um, you know, maybe I'm trying to pursue this path that I'm on and see my potential through in his honor, 'cause he really sacrificed a lot.

GATES: Perhaps because of his sacrifices, Najme chose to focus on the future, not on the past.

And rarely discussed the life he'd left behind in India.

We set out to recover it.

Beginning in Sherkot, the city in northern India, where his mother's family has deep roots.

Have you ever seen that photo?

MINHAJ: No.

GATES: That photo was taken at your grandmother's house in Sherkot sometime around 1948.

So that's two years before your father was born.

MINHAJ: Wow.

This is a beautiful place.

I mean, like, if you look at the, the archway of that, that's incredible.

GATES: Well, guess what?

Your father told us that in the back of the house, there were quarters to house elephants.

MINHAJ: What?

GATES: Yes.

And your aunt remembers that they own two adult elephants and a baby elephant.

MINHAJ: What do you mean they owned elephant?

They just had elephants?

GATES: Yeah, I mean, like, you have a dog, do you have a dog, a cat?

MINHAJ: No, I don't have a dog; we have a rabbit.

GATES: They had elephants.

MINHAJ: This is so weird because when I was a kid, I asked my dad, well, my sister really wanted a dog.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: And he was like, “No pets, we have Hasan.” (laughs).

And his, he had a, in his family, they had elephants.

GATES: Three; two adults and a baby at the time that photograph was taken.

MINHAJ: Oh my God.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: That's awesome, that's really cool.

GATES: I think it's cool.

MINHAJ: That's so cool.

GATES: We wanted to learn more about Najme's family, but we faced a huge roadblock.

Few historical records survive in northern India, and those that exist are often difficult to locate because they lack filing systems or indexes.

This problem is compounded by the fact that the widespread use of permanent surnames within India is relatively new.

And many unrelated families share the same surname because they were initially derived from trades or professions.

So doing genealogy in this part of the world can be extraordinarily tricky.

But we got lucky when we discovered that the surname of Hasan's grandmother is Begum, which has unusual roots.

Did you know that?

MINHAJ: No.

GATES: Begum is an Urdu word, uh, with roots in a Turkish word for “princess.” And historically, it was given to women who were the wife or daughter of a Beg, meaning a Lord or a chieftain.

Ever thought of your family as maybe having royal roots?

I know in your fantasy, when you look at a mirror, you see a prince.

But... (laughs).

MINHAJ: Um, you know, I got cousins that have egos like that, but, but I don't know if we, we are related in that way.

Well, we didn't find any evidence that any of your ancestors were royalty, except etymologically.

But it's certainly possible because of that, that they were... MINHAJ: Mmm.

GATES: What's it like to think about that?

MINHAJ: It's pretty incredible.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Yeah.

And it's pretty amazing to just understand who you are and where you come from and what generations before may have been doing.

GATES: Mm, it is.

MINHAJ: Yeah.

GATES: Riding around on those elephants in the backyard.

MINHAJ: Yeah, riding elephants, sure, yeah.

GATES: Though we couldn't connect Hasan's family to royalty, we did uncover something fascinating.

Hasan's relatives told us that his great-grandfather, a man named Sibghat Ullah, was a prominent landowner, and as we combed through the archives in his home region, we uncovered a British publication that seemed to confirm this.

MINHAJ: "The town of Dhampur..." GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: "...is the seat of several well-known families who own land."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: “Mohammed Sibghat Ullah, the principal sheik resident of the place.” GATES: That name sound familiar?

MINHAJ: That's my great-grandfather.

GATES: We can't be certain, but we spoke with a scholar about this at length, and we think this may be indeed your great-grandfather.

The names are similar, and Dhampur is about five miles from Sherkot.

MINHAJ: Wow, and this is from a newspaper.

GATES: “The Bijnor Gazetteer.” MINHAJ: Yeah.

GATES: Which is a geographical index.

MINHAJ: Yeah, Bijnor, my dad has talked about Bijnor just casually.

GATES: Oh yeah?

MINHAJ: When he talks about Sherkot and Bijnor, but it, it just sounds like he's describing different regions from “Game of Thrones.” GATES: Huh.

MINHAJ: I'm like, I, I don't know what that territory is.

(laughing).

GATES: This index not only indicates that Sibghat owned land, it also describes him as being the principal sheikh of his town, which was potentially a very significant find.

The term “Sheikh” refers to a social class of Muslims in northern India, a group that claims Arab descent through the Prophet Muhammad and two of the founding Caliphs of Islam, Abu Bakr and Umar.

Did you ever think you might have Arabic roots?

MINHAJ: No.

GATES: What's it like to think of that possibility?

MINHAJ: That's, um, I, you know, in our faith, the, the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, and, um, Abu Bakr and Umar the Khalifa are extremely important in our faith.

GATES: Yeah.

MINHAJ: And they're like the tent poles of what became Islam and the spread of Islam around the world, so... GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: No, this is, um, this is extremely, um, very powerful and very, um... I had no idea.

GATES: There were no records to test this theory, so we turned to DNA.

While most modern-day Indians do not have any genetic ties to the Arab world, Hasan's admixture reveals that 2.3% of his DNA comes from West Asia, which includes what is now Iran, and 0.3% comes from the Arabian Peninsula.

That is a significant result.

So, you have a DNA connection to Iran and to the Arab world.

For most other Indians... MINHAJ: Oh, wow.

GATES: So, what's it like to learn this?

MINHAJ: Yeah, this is very powerful stuff, uh, both spiritually and historically.

GATES: Yeah, what's your father gonna say?

MINHAJ: Oh, he is gonna, he's gonna love this, this is gonna blow my dad's mind.

This is gonna mean, uh, I can't, I cannot tell you this is gonna mean so much to my, my family.

It means so much to me.

GATES: We had one more detail to share with Hasan, it concerns what's called the First Battle of Panipat.

The battle was fought near the city of Delhi in April of 1526 and marked the start of the Mughal Empire, the last Islamic Empire to rule India.

It's a seminal event memorialized in countless poems and paintings... and you may well have had an ancestor who fought in that battle.

It's pretty cool.

(laughs).

MINHAJ: Yeah, this is a wild painting.

GATES: Yeah, it's totally wild.

MINHAJ: Yeah, there's like guys on horseback.

There's a dude getting beheaded, but it's very beautiful, the, the, it's, the painting is very beautiful.

GATES: But what's it like to think of that possibility and to be introduced to the complexity of your genetic makeup?

MINHAJ: I mean, it's surreal, this is one of the most epic stories of, you know, the greater Indian subcontinent in its history.

GATES: Yeah.

MINHAJ: When you go to Delhi, you can still see those old Mughal forts.

GATES: Yeah.

MINHAJ: And so, to know that we have a connection to that is pretty epic.

GATES: Does it change the way you, you see your father?

MINHAJ: 100%.

GATES: Yeah.

MINHAJ: Yeah.

This is, uh... This is, um... yeah, there's a level of depth to this that I did not anticipate.

GATES: Much like Hasan, Lizzy Caplan was about to discover a hidden depth to her family.

The story begins on her mother's side with Lizzy's great-grandfather, a man named Abraham Lajb Miodownik.

Abraham was born sometime around 1892 in what was then the Russian Empire.

But he didn't stay in Russia for long.

We found him in New York City when he was 19 years old, applying for American citizenship.

CAPLAN: That's amazing.

That's amazing.

19.

That's crazy.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

CAPLAN: I've tried to, you know, imagine what that would, you know, I, I haven't spent a ton of time trying to imagine it, but I have thought about, you know, what would it be like to be on a boat coming to a place where you knew nobody, not a soul.

And for whatever reason, I never imagined it as a, a 19-year-old kid.

And I know 19 was different then than it is now, but man, I, just, like, children having to make these monumental decisions.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: It's wild.

GATES: We don't know what motivated Abraham to come to America, but that decision forever altered his life.

And we found the passenger list of the ship that brought him here, giving Lizzy a glimpse of her ancestor at that crucial moment.

CAPLAN: Name in full: Abram, uh, Miodownik.

Nationality: Russia.

Race or people, Hebrew.

Whether in possession of $50 and if less, how much, $3.

Whether going to join a relative?

Sister, Anna Miodownik.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: New York, 16th East, 118th Street.

GATES: That is Abraham arriving in the United States of America.

CAPLAN: So, does this say he had $3?

GATES: Yep.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: It says, “Do you have at least $50?” He answered “No.” “How much do you have?” “I have $3.” He came here with three bucks.

CAPLAN: Unreal.

I mean, yeah, I don't even, like, how do you even... you make this decision because you have no other choice, I suppose, many situations, but that, that, I mean, just the, the idea that he was coming to join his sister, who I've never heard of.

And even just the, the correspondence that would be required to make those plans and how long that would take... GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: ...and how... I mean, it's, it's crazy.

I keep saying that, but it's crazy, it's crazy.

GATES: We now set out to learn about Abraham's life before he immigrated.

Lizzy had long been told that her mother's ancestors were Russian Jews.

But that was not exactly true.

At the time of Abraham's birth, Russia was a vast empire covering much of Eastern Europe.

And Abraham's hometown was a village called Zawiercie.

It lies on land that we no longer consider to be Russian.

Have you ever heard of this place?

CAPLAN: No.

GATES: That is your family home.

It's located in the south of modern-day Poland.

CAPLAN: Huh?

GATES: So you, you've thought of yourself as Russian.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: Did you ever think of yourself as Polish?

CAPLAN: No.

GATES: You're Polish.

CAPLAN: Yeah!

GATES: You gonna visit?

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: Yeah.

CAPLAN: I'm booking my, I'm booking my flight.

GATES: You got deep roots there.

CAPLAN: I know.

When Lizzy visits Abraham's hometown, she will likely find few traces of the world he knew, as it was almost completely obliterated by wars in the first half of the 20th century.

But in the Polish State Archives, we found documents that help bring Abraham's world briefly back to life.

CAPLAN: “On the 24th of August, 1890, came in, Beniamin Miodownik, baker from the village of Zawiercie, 33 years old, and presented a male infant stating that he was born in Zawiercie on August 17th of this year to his lawful wife, Dobra Zysla.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: “The child is circumcised and given the name Abram Lajb.” GATES: Mm-hmm, that is your great grandfather's birth certificate.

CAPLAN: 1890, crazy.

GATES: Yep, and Beniamin and Dobra are your great-great-grandparents; you have DNA from these people.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: These are your biological kin.

And we're back in Poland, over 130 years ago.

What's it like to see that?

CAPLAN: Yeah, I mean, look, I'm sure he'd be thrilled to share the information that he was circumcised on television 130 years later.

Yeah, it's, it's, it's like I, yeah, in a village, he was a baker.

It's just, this is like a... GATES: Did you know you had any bakers in the family?

CAPLAN: No, although... GATES: Can you bake?

CAPLAN: Probably could've guessed.

GATES: Can you bake?

CAPLAN: Yeah, of course.

GATES: Okay.

Abraham's parents, Beniamin and Dobra, were married in 1883.

By 1900, they had had at least six children together, but their happiness didn't last.

Dobra died on August 23rd, 1900, six days after giving birth.

CAPLAN: Wow.

GATES: Dobra was just 40 years old, and she left seven children behind, including a newborn baby.

Can you imagine?

CAPLAN: No, of course not.

I mean, no, I don't even know, like, what is a baker, I, I hope that there was other family around.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: I'm also just thinking about this, yeah, Abe, Abe being so young... GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: And losing his mom, oof.

GATES: Abraham lost his mother when he was just 10 years old.

He was three years younger than you.

CAPLAN: Mm-hmm.

GATES: When you lost your mother, how do you imagine this loss affected him?

CAPLAN: I imagine that there probably wasn't a lot of time to talk about how it affected him... GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: ...at the time, I imagine that would be very, very lonely.

GATES: Yeah.

And how about Dobra's husband, Beniamin?

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: How do you think he coped?

He was left alone with seven children, including a newborn baby.

CAPLAN: A newborn.

I know, how, I mean, but yeah, as, I mean, women, I'm sure, you know, dying in childbirth, yeah, I have never really thought that through, that the infant is then left with the father.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: In 1900.

(laughs).

How, I don't know how you would cope, how one would cope.

GATES: I can't even imagine.

CAPLAN: Uh, completely can't imagine.

GATES: There is, of course, no way to know how Beniamin processed his loss.

But we do know that he moved on.

Soon after Dobra's death, he remarried and transplanted his family to the town of Czestochowa, about 30 miles away.

Your great-grandfather Abraham would leave for America from there in the summer of 1906.

CAPLAN: Wow.

GATES: He likely never saw his father again, what do you think that was like for him?

CAPLAN: I just, I can't even begin to fathom what that family relationship would be like with all of those kids.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: Um, very limited resources.

I mean, who knows?

You can only like, speculate what he thought about his own mother, let alone this stepmother.

Um, maybe it was lovely, and it was horrible to leave, and maybe it was horrible, and it was a great escape.

GATES: “I'm outta here.” CAPLAN: Yeah, I mean, who could... we'll never, never know.

Wow.

GATES: Lizzy, let's just take a moment to think about the sheer magnitude of your great-grandfather Abraham's decision to move to the United States with how much in his pocket?

CAPLAN: $3.

GATES: $3.

That singular brave decision completely changed his fate and, by extension, your fate.

CAPLAN: Yep.

GATES: Think about what could have happened had he decided, uh, “I don't speak English.” “I ain't got no money,” you know, “I like, uh, the vodka here.” CAPLAN: Yeah.

(laughter).

GATES: You know?

What's it like to realize that, to think about that, you know, "Two roads diverged in a yellow wood..." you know?

CAPLAN: Yep, that's it, right?

GATES: Yeah.

CAPLAN: It's, you are the product of a bunch of decisions made by people that you've never met before.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: It's impossible not to think that there's some kind of cosmic plan or fate or something.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: And even if it's all just random, it's still miraculous.

GATES: We'd already traced Hasan Minhaj's father's roots, revealing a surprising connection to Islamic India in the 1500s.

Now turning to his mother's family, we found a surprise in the much more recent past.

The story begins with Hasan's grandmother, a woman named Tausif Rizvi.

Hasan remembers her as a stern, but loving disciplinarian who rarely spoke about her own childhood.

And we think we know why.

Tausif was born in Meerut, a district in northern India.

Her parents were farmers, but she wasn't raised by her parents.

Instead, soon after her birth, she was adopted by her mother's childless elder sister.

MINHAJ: So, you're telling me my grandmother, Tausif Rizvi... GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Was raised by... GATES: Her aunt.

MINHAJ: Wow.

She was a sign-and-trade, like in the NBA.

(laughs).

GATES: And you've never heard this story before?

MINHAJ: No, I've never heard this story before.

GATES: It's like a fairytale.

MINHAJ: Yeah.

GATES: This adoption would affect Tausif in ways her family never could have predicted.

At the time, India was a colony of Great Britain, ruled by a government, informally known as The Raj.

And Tousif's aunt was married to a doctor who spent much of his career working for the Raj, including two terms in a government-run jail.

We found a description of the jail, offering a glimpse into Tausif's highly unusual childhood.

MINHAJ: “The district jail is at Rajbari and civil lines.

It was formed out of some of the abandoned barracks, and is somewhat larger than most of the Oudh jails having been originally designed as a divisional jail.

It is, as usual, under the charge of the civil surgeon.” GATES: According to your family, your grandmother and her parents lived in a government house next to the jail, with inmates doing chores in their home and even growing their vegetables.

MINHAJ: This explains why she was so strict with me.

GATES: Could be.

Your grandmother never talked about this?

MINHAJ: Never talked about this, no.

GATES: Do you know what “civil lines” refers to?

MINHAJ: I have no idea.

GATES: Well, under the Raj, civil lines were areas within cities where the British Civil Administration resided.

MINHAJ: Wow.

GATES: Where the White people lived.

British officers and administrators lived within them in European -style bungalows.

Same in Africa.

Tea was served on verandas, and leisure activities included horseback riding and, of course, cricket.

And the only Indians permitted to live in civil lines were household staff or high-ranking Indian officials, such as judges and doctors.

So, your family was living alongside the British in these compounds.

MINHAJ: Wow.

GATES: So, what do you think that was like for your grandmother?

MINHAJ: I could only imagine that, I mean, for my, for my Nani code switching and going between two worlds and trying to understand how to navigate both, certainly probably shaped her... GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: ...understanding of how to survive and make it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Um, she definitely made sure that on my mom's side, everybody was extremely educated.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: So, I'm sure that living within these civil lines shaped perhaps her emphasis on education.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: Like, this is the way you make it, and this is how you succeed.

GATES: Hasan is not alone in his opinion of Tousif.

His family gave us a poem that she memorized as a child.

It was written by her adoptive father and recited by her at a school function to mark the departure of one of her teachers.

Antiquated, yet entertaining, the poem shows her immense enthusiasm for her own education.

MINHAJ: “This news is dreadful.

What will happen to me after your departure, you are indeed leaving.

But please forgive me if I was ever insolent after receiving your guidance.

I understand the teacher -student relationship.

Once respectful manners are learned, a little jest is allowed.

Who will now teach arithmetic, algebra, and history like you?

Examinations are near, and you are no longer here.

Remember this always, it is praise for you.

My writing is a small token of appreciation.” (laughs).

So, this, this is two things, like, to me, number one, you know, kudos to her guts to stand up on stage.

GATES: Sure.

MINHAJ: Um, number two, this is definitive proof that Indians in our DNA are teachers' pets.

This is the most overachieving, pick me, can I get extra credit, "Dear Professor" energy.

Which is why it's so crazy that I'm a comedian.

Like this is, this is the, you know, this is, this is in my blood.

GATES: Your family told us that your grandma could still recite that poem... MINHAJ: Yes.

GATES: ...from memory at the age of 93.

MINHAJ: Yes.

GATES: That's amazing.

MINHAJ: Yeah.

GATES: How does it feel to read this, is that the first time you've read it?

MINHAJ: This is the first time I've read it; this is the second time I've heard it.

The first time my uncle performed it.

GATES: Oh, that's cool.

MINHAJ: And it was really beautiful to hear him perform it.

GATES: Did you know that your grandmother went to a high school that had only 10 female students?

MINHAJ: No.

GATES: She studied arithmetic, English, Hindi, history, geography, and Urdu, and even played badminton.

MINHAJ: I didn't know, I didn't know that GATES: Isn't that cool?

MINHAJ: Yeah, yeah, 'cause by the time, you know, I got to know her.

She was, she was a, a small, you know, the way all grandmothers are, she was just a Golgappa at that point, you know, she's like a small, cute little round babushka.

GATES: She graduated in 1946 and then went back to Zunheboto and where she married your grandfather in 1950.

MINHAJ: Wow.

GATES: She had a tumultuous childhood, but she persevered and thrived.

You feel a connection?

MINHAJ: I feel a huge connection to her, and she, um, regularly during my birthdays would give me money for my birthday present.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: But it, it could only be used to buy something that would help me in my pursuits.

GATES: Mm.

MINHAJ: So, she helped me buy my first MacBook Pro that I edited my first sketches on.

GATES: Oh, yeah?

MINHAJ: Yeah, so that's because of my... GATES: Oh, that's cool.

MINHAJ: ...my grandmother, yeah.

GATES: We had one more story to share with Hasan returning to Tausif's hometown in Maroth, we were able to trace her husband's roots back two generations and place Hasan's ancestors at ground zero for what's often called India's First War of Independence.

A troop rebellion against the British that led to uprisings across the nation.

Though it was ultimately crushed, the rebellion lives on in memory, even to this day, and it began in Meerut.

So how does it feel to know that you have ancestors, your third great-grandparents, who may have been there at the very start?

MINHAJ: It's really powerful, and, um, I'm out here complaining when the Wi-Fi goes down.

(laughs).

But in all seriousness, it's like I can only imagine what they witnessed and what they went through and saw in their life.

And, um, it makes me feel really proud.

And I feel, um, really overwhelmed with gratitude and humility that this is my family and I'm lucky enough to be their great-great- great-grandson.

GATES: We'd already traced Lizzy Caplan's mother's roots from Poland to New York, revealing how her great-grandfather Abraham came to America.

We now turn to a darker side of this story.

In 1926, Abraham's younger brother, a man named Wolf Miodownik, moved from Poland to Belgium, likely hoping to find the kind of opportunities that had drawn Abraham to the United States.

But those hopes would be dashed.

On May 10th, 1940, Belgium was invaded by Nazi Germany.

Wolf was 30 years old at the time.

His wife Leiba was 23.

Can you imagine?

CAPLAN: No.

Genuinely, no.

Um, just what a terrifying time.

GATES: Did you ever think you had a personal familial connection to this?

CAPLAN: I thought maybe it was odd that I didn't.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: But, um, so I, I guess it's with all of the siblings, it's, it's not completely surprising, but I do, you know, growing up, it was my friends whose grandparents had survived the Holocaust, and we were very aware of who those grandparents were, and my grandparents were not in that group.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: So, this is news to me.

GATES: Wolf and Leiba are Lizzy's great-grand uncle and aunt, and though the details of their story were not passed down, its outlines would prove painfully familiar.

After the German invasion, they watched helplessly as the Nazis began seizing Jewish property and implementing anti-Semitic laws.

Then, in March of 1944, just months after the birth of their first child, the family was arrested, and their situation became unimaginably worse.

They were sent to a transit camp in northern Belgium called Mechelen, and then they were put on a train called “Transport number 24.” And guess where transport number 24 was heading?

CAPLAN: I, uh, God, I, where, I don't even where, where?

GATES: Please turn the page.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

GATES: Auschwitz.

CAPLAN: Yeah, I had no idea I had relatives in Auschwitz.

Ugh, yeah, it's, it's so awful.

And you see, like in these pictures, which I've seen so many times, so many kids, and yeah, it's, uh, it is different when it's your own, when you know it's your own people, family.

GATES: Roughly 1.1 million people were murdered in Auschwitz.

The vast majority were killed upon arrival in gas chambers.

The rest were consigned to slave labor and generally died of starvation or disease.

Precise records were not kept, but the fates of the people on Transport 24 are set down in what's known as the “Auschwitz Chronicle.” A documentation of daily life in the camp written by a Polish historian, most were immediately sent to the gas chambers.

A small percentage were selected for labor, and none of the 54 children who were on this transport appeared to have been admitted to the camp.

So, you know what that means?

CAPLAN: Ugh.

Oh my God, that's so horrible, yeah, that's so horrible.

I just, I, yeah, I don't know how you exist in that much fear, and then I don't know how you recover from, or forget recover, but like, go on from that.

What, and what would be worse if they, if they were selected to work or if they were, I don't know how, I mean, somebody takes your baby from you.

I just... GATES: You know, ripping the baby out of your arms, Wolf's six-month- old son, Beniamin, was likely killed immediately upon arrival.

And since he was so young, could not walk, his mother Leiba would've likely gone to her death alongside him.

CAPLAN: Just to carry him in.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: Ah.

GATES: "You two go this way, take your baby..." and you lure them in.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

And I'm, God, it's so, it's like, it's like such a, uh, there's no good outcome here, no matter what, I'm glad though to hear they were together, mother and son.

GATES: With his family dead, Wolf entered Auschwitz on his own.

Incredibly, he would survive for more than eight months, only to face another horrifying ordeal.

In January of 1945, with the war almost over, and Russian armies advancing across Poland, the Nazis were desperately trying to cover up their crimes.

Auschwitz was abandoned, and Wolf was eventually transferred to Bergen-Belsen, a notorious concentration camp in northern Germany.

From there, he was shipped some 400 miles south to Dachau, yet another camp.

So, how do you think Wolf found the strength to keep going?

CAPLAN: I don't know, that's just human will to survive, 'cause like, what is this life?

GATES: Mm.

CAPLAN: Why would you want to keep going?

Just like shuttled from one of these horror shows to the next?

It's... GATES: And just think of the terror.

CAPLAN: That's it, right?

GATES: Yeah.

CAPLAN: Constant, constant terror.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: With no end in sight.

I, yeah... they were, they were tougher than we were, than we are.

Dachau was liberated on April 29th, 1945, almost two months after Wolf arrived.

He was likely emaciated and very close to death.

But as it turns out, Wolf had a great deal, more life left in him.

After the war, Wolf returned to Belgium, where he married a fellow Holocaust survivor.

They welcomed a daughter in 1949, and then three years later, moved one final time to America.

CAPLAN: “Wolf Miodownik, nationality, stateless.

Race, Hebrew.

Age 41.

Final destination in United States, Mr.

Charles Meadow, 1138 Wooster Street.” God, it's so crazy to see just like the map of the concentration camps and then Wooster in LA.

Like that's crazy.

GATES: Yeah.

CAPLAN: Yeah, that's, that's pretty nuts.

GATES: It's a miracle.

CAPLAN: It is.

Absolutely.

GATES: Wolf was 42 years old when he arrived in the United States.

Incredibly, he had survived at least four concentration camps and lost a wife and a child, as well as countless friends and relatives.

But he was able to build a new life for himself.

A life that would be celebrated right up until the end, as evidenced even by his grave.

CAPLAN: Wow.

GATES: Wolf lived to be 93 years old.

CAPLAN: Nice Wolf.

GATES: He died November 10th, 2003, and is buried along with his second wife, Mala, in Coma, California, just outside of San Francisco.

CAPLAN: Golden Mensch.

GATES: How about that?

CAPLAN: I love it.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

CAPLAN: Oh, this makes me so happy, 'cause like he's got little funny things on his... GATES: Yeah.

CAPLAN: ...on his Tombstone.

Like that's... GATES: He was loved.

CAPLAN: Yeah.

They both were.

Oh my God, this is amazing.

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for Lizzy and Hasan; it was time to unfurl their full family trees, now filled with people whose names they'd never heard before.

CAPLAN: That's incredible.

GATES: For each, it was a moment of awe.

CAPLAN: Wow.

GATES: Offering the chance to reflect on the sacrifices that shaped their families and forged their identities.

MINHAJ: When you see your parents struggling and working hard and clipping out coupons... GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: ...you don't think you're someone... ...or from somewhere.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: You know, you just think you're scraping by and surviving.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

MINHAJ: But when you see stuff like this, you're like, maybe I'm part of something bigger.

CAPLAN: The only way that I'm sitting here now is because of the decisions that they were either forced to make or that they chose to make.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

CAPLAN: And I feel very lucky, like in the dictionary definition of the word “lucky” that they made those decisions.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Hasan Minhaj and Lizzy Caplan.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of “Finding Your Roots.”

Hasan Minhaj Learns of His Royal Roots

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep4 | 4m 9s | Hasan discovers the possibility that he may have royal roots in Northern India. (4m 9s)

Lizzy Caplan's Ancestor Immigrated To New York With Three Dollars

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep4 | 4m 9s | Lizzy contemplates the difficult decision her ancestor made upon immigrating to New York. (4m 9s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep4 | 30s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the roots of actor Lizzy Caplan and comedian Hasan Minhaj. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: